“To Belong to Not To Belong? Embodied Borders and the Politics of Sex and Gender Knowledge in Anti-Trans Feminist Discourses“

Where I’m at Currently:

Final year of funding via the Elsa Neumann Stipendium, projected finishing date is July 2026.

Finished Chapters include “Sociology and Transgender Studies: a Destabilizing Enterprise”, “Trans/Feminism: Mapping the Contours of a Contested Terrain”, “Situated Disobedience: Power, Discourse, and the Borders of Belonging”, and “Lines of Struggle, Practices of Refusal: Inquiry as Situated Disobedience”.

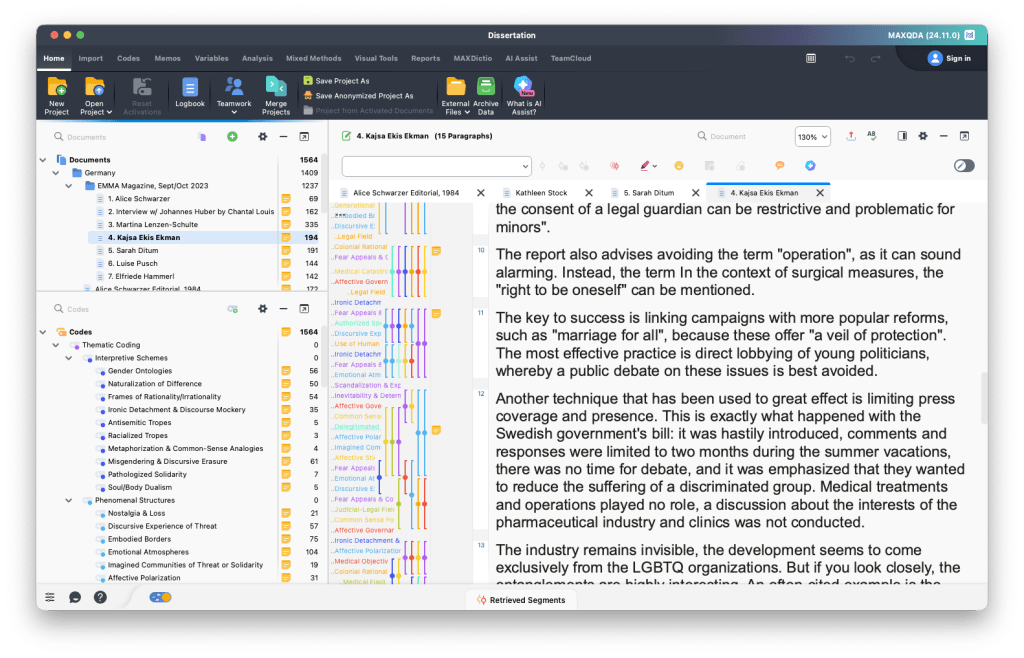

September 2025: data analysis in progress. Starting with texts from October 2023 issue of German feminist magazine EMMA. Mastering use of MAXQDA.

October 2025: continuing data analysis with UK and USA cases (Kathleen Stock, JK Rowling, TransSisters, & dirtywhiteboi67

February 2026:

– Results/Analysis/Discussion chapter written, sent to supervisor for review and edits.

– Completed final review and edit for Chapter 2.

– Rewrite and edits for Chapter 3, lit review in progress.

– Final Edits for Chapter 4, theory, in progress; sent to 2nd supervisor for review.

– Final Edits for Chapter 5, methodology in progress.

Table of Contents following the research project proposal.

Abstract

Colloquially known as the “TERF (Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminist) Wars”, this dissertation project will examine the decades-long social, political, and academic debates between feminists surrounding transgender identity and the concepts of sex and gender. As scholars such as Hines (2020), Pearce et al. (2020), and Williams (2020) have discussed, there is a history of anti-trans sentiment in feminism dating back to the mid 1960’s in the United States, after which it was adopted by UK and Australian feminists and has recently spread across the globe from Latin America to Africa and Central Asia (Cammings, 2020). In effort to consolidate the rapidly growing body of research surrounding anti-trans discourse, I aim to first provide a thorough overview of literature on the topic of Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminism, or Gender Critical Feminism as has now become known. Drawing from a data set that includes academic texts and books and utilizing the Sociology of Knowledge Approach to Discourse, I will (1) identify and reconstruct different anti-trans feminist discourses in the US and the UK, (2) examine their content-related structuring in regards to how they define and discuss sex, gender, and transgender identity and their political implications in both the US and the UK, and (3) engage with the decolonial concepts of the politics of belonging (Yuval-Davis, 2006) and Gloria Anzaldúa’s “Borderlands/La Frontera” (2007) to discuss how belonging and identity are negotiated in the discourses and uncover knowledge/power regimes that reside in this type of feminist thinking in effort to overcome anti-trans perspectives in feminist theory and affect positive political action.

Introduction

Time Magazine’s 2014 cover featured Laverne Cox, a black transgender woman and activist actress in the US, marking what trans feminist scholars have referred to as the “Transgender Tipping Point” (Pearce et al., 2020) where LGBTQ activism and scholarship began centering transgender narratives and transgender rights. News and social media gave more visibility to transgender people and the demands for social, political, medical and legal inclusion took center stage not only in the US, but the UK as well. The increased visibility of transgender people and their demands for access to, and inclusion in, sex-segregated spaces are being met with equal force in the form of transphobic discourse on social media, in print, on university campuses, and through coordinated organizational political efforts from a growing body of feminist activists. In 2017, British Prime Minister Theresa May announced the government’s plans to reform the 2004 Gender Recognition Act (which would allow transgender UK citizens to self-identify their legal sex without having to prove to the state that they meet a set of pathologizing medical requirements), which Pearce et al. (2020) note caused “a significant upsurge in public anti-trans sentiment” (p.678). Over 100 “bathroom bills” have been proposed or put into law in the United States in 2022 that will forbid transgender and gender non-conforming people from using the restroom that correlates with their gender identity.

The increased visibility of transgender people and their demands for access to, and inclusion in, sex-segregated spaces are being met with equal force in the form of transphobic discourse on social media, in print, on university campuses, and through coordinated organizational political efforts from a growing body of feminist activists. These feminist activists, journalists, authors, and academics that are pushing back against what they call ‘transgender ideology’ – “the belief that who a person feels they are, is more important than the material reality of their body” (Freeman, 2022) – which they see as politically in conflict with women’s sex-based rights. A recent post in the UK-based group Mayday4Women claimed “Transgenderism [sic] is currently one of the biggest threats to feminism in the UK” (Tudor, 2021 p.244). The LGB Alliance, a British organization founded in 2018 to oppose the GRA reform, stands “in total solidarity with millions of women concerned that their rights are being eroded in the pursuit of a strange ideology that has no place in our laws” (n.d.) and now has chapters in over 15 different countries. One of the biggest news stories in UK media in 2020 was J.K. Rowling’s twitter feed being filled with claims questioning transgender people’s legitimacy in the public sphere and their right to identify as men and women. But as mentioned earlier, these are not new conflicts within feminism – they began with the 1979 publication of Janice Raymond’s “The Transsexual Empire” and have steadily been present in feminist activism since.

As right wing anti-gender movements spread across the US and the UK and seek to roll back rights for women and LGBTQ people, the mobilization against transgender rights, which is coming from people who call themselves feminists, is very concerning. Whereas the Catholic Church and right-wing populist leaders are leading a moralistic charge against gender (being transgender is sinful, it’s disgusting, etc); the feminist mobilization is employing an epistemological force. That is, their anti-“gender ideology” agenda is about questioning how we know what we know in the world – are transgender men and women really who they say they are – men and women, male and female? and just what is gender, what is sex? These are contemporary phenomena with deep historical roots, which must be interrogated to make sense of the current landscape. My research will focus on looking at several literary texts and academic publications produced by anti-trans feminists and deconstruct the discourses in order to construct a theoretical approach in which we have a reconciliation between feminists in the debates about sex and gender. Such a project as this would provide an important contribution to sociology, not only because it will offer us an insight into the production of ideologically fixed, anti-evidential politics, but also because of what we can learn about power relations (Vincent et al., 2020) rooted in Western imperialism and colonialsm. Additionally, just how these discourses impact marginalized people makes it a meaningful element of sociological inquiry. In what follows, I will briefly review literature on anti-trans feminism, outline my aims and objectives, and discuss my methodology.

Brief Review of Literature

In order to justify the academic need and relevance for this project, I must emphasize that there is a significant amount of literature being currently produced surrounding the subject of anti-trans feminisms. A significant portion of my dissertation will be devoted to a review and thorough analysis of what has already been discussed in order to synthesize our sociological understanding of their theories and politics. Prior scholarly work on the subject of Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminism (in Sociology, Gender Studies, and Philosophy) has focused on unpacking concepts of Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminism in the US and the UK and on countering the claims made by them. These include topics such as the validity of Rapid Onset Gender Dysphoria (a mental health diagnosis that has been criticized due to a lack of reputable scientific evidence), detransition (see Hildebrand-Chupp, 2018), and single sex spaces like bathrooms (see Jones & Slater, 2020). In my Masters thesis, I used a critical discourse analysis approach to “unsettling” the anti-transgender gender discourse by examining it through Maria Lugonés’s theoretical framework of the coloniality of gender, revealing how transgender subjects are shaped by anti-trans ideology through a colonial system of gender domination that privileges a Eurocentric understanding of sex and gender.

As Hines (2020) sharply points out, these debates in feminism and attacks on transgender rights entail ideas about the “truth” of the sexed body and morality tales and origin myths about telling the “truth” of gender. I envision this dissertation project as one that will get to the root of these knowledge claims. There is a rapidly expanding body of literature discussing gender critical/trans exclusionary radical feminism, making it hard to keep up with contemporary research on the subject. This is why I would like to begin my dissertation by doing a systematic literature review of the work that discusses Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminism in the US and the UK, as it has yet to be done before. I believe a lot of these works would benefit from being brought into conversation with each other, and rigorously analyzed and evaluated in order to be sufficient for theory building.

Dr. Sally Hines is one of the most cited academics working in the field of contemporary transgender studies in sociology and has written extensively on the subject of transgender people and feminism. In her 2020 article “Sex wars and (trans) gender panics: Identity politics in contemporary UK feminism”, Hines explores gendered shifts through the lenses of identity and embodiment, discussing important moments in feminist politics and theorizing where certainties have become undone. These ruptures emerged over whether or not the physical, sexed body was the ultimate source of women’s oppression, as was the rallying cry for of second wave feminist. Hines explains how feminism entered a third wave, where the social construction of gender and sex took precedence over biologically essentialist understandings of womanhood. This caused quite a bit of turmoil in the push for the legal rights of transgender individuals in the UK in the new millennium, as being able to change one’s gender marker via self identification (rather than having a medical doctor approve the change) was in the process of being decided by the government through the Gender Recognition Act reforms.

The backlash to the reforms of the GRA were driven by anti-trans feminists who argued that allowing a transgender person to self-declare their gender will reduce the safety and well- being of cis women. They politically campaigned for women’s ‘sex-based rights’, proposing a reinstatement of sex as the main source of women’s oppressions in effort to push back against trans rights, as well as putting reproductive function as the primary and fundamental site of women’s disadvantage. As Armitage (2020) points out in his article explaining media backlash to transgender people in the context of the reform, a trans moral panic has propagated through mainstream and social media, creating misinformed beliefs about trans people. The notion of deception, that trans women are pretending to women and trans men are pretending to be men, runs through their denouncements of trans people. Armitage shows how trans people have been constructed in the public image in terms of a threat – “to investment in gendered norms, to one’s own gender identity, and to [LGBT and women’s] in group resources and desires for assimilation into mainstream culture” (2020, p.11). For the GCF, sex is defined by genitals, reproductive organs, chromosomes, and hormonal makeup, while gender is characterized as identity. And while gender may be subject to change, sex is fixed. In the eyes of GCFs, one can ‘identify as’ a man or woman, but will never really actually be a man or woman. Hines critiques their biological sex based oppression standpoint, writing that “the positioning of sex as the source of oppression presumes a universal characteristic of womanhood in which all cis women are disadvantaged in the same way” (2020:708). And as Black feminist thought has made clear, gender does not operate in isolation – not all women experience gender oppression in the same way and a specific biology does not solely determine oppression. Emily Hotine (2021) makes this very clear in her text “Biology, Society, and Sex: deconstructing anti-trans rhetoric” when she argues that “discrimination does not need to be rooted in biology to be real … [GCF is a] brand of feminism that concerns itself with the middle class white woman … their ideology is founded on logic that does not allow for the inclusion of Black women as Black women” (p.4).

Locating trans people outside of the categories of woman (and man) and debating their place in the public and political realm has led to what Vincent et al. (2020) call the “Ti”. Debates about whether trans women belong in women’s spaces such as bathrooms, changing rooms, and spas led to increasing media coverage and public commentary on trans people’s bodies. In their excellent piece from TERF Wars (2020), The Toilet debate: stalling trans possibilities and defending ‘women’s protected spaces’, Jones and Slater (2020) consider how the toilet has become an unexpected focus of feminism in the UK. The authors critique the GCF position of trans exclusion in toilets based on their cis- centric, heteronormative, and gender essentialist positions, which include the perpetuation of explicitly transmisogynist discourses. While epistemologies and ontologies of gender and sex are not restricted to the toilet, it is a curiously productive space for gatekeeping (Jones & Slater, 2020). Arguing that access to safe and comfortable toilets plays an integral role in making trans lives possible, as well as anyone who doesn’t conform to gender stereotypes, Jones and Slater highlight how dangerous the policing of gender can be in the homogenization of womanhood. Jack Halberstam (1998) was the first to point out how gender policing in bathrooms affects cis women who are masculine. In what way, and by whom, can body parts and genetic make-up of strangers in these spaces be observed and regulated? These moves by gender critical feminists to restrict access to single-sex spaces “highlight the white Western-centric lens through which gender is, literally, seen, and reinstated by misogynistic tropes of how women’s bodies should appear in order to be recognized and valued” (Hines, 2020 p.713). Moving throughout the rest of Vincent et. al’s (2020) TERF Wars book, we have texts that further analyze the topics of trans and feminism today. In Autogynephilia: a scientific review, feminist analysis, and alternative ‘embodiment fantasies’ model, Julia Serano critiques the theory of autogynephilia (that trans women’s identities are just a by-product of their sexual orientation resulting from an eroticization of being a woman) and demonstrates how gender critical feminists use this essentialist, heteronormative, male-centered theory of womanhood to discredit their identity as women. Serrano (2020) discusses how it first entered trans exclusionary discourse by way of Sheila Jeffreys and has become a recurring talking point on gender critical websites to insinuate that trans women are just ‘sexually deviant men’. In More than ‘canaries in the gender coal mine’: a transfeminist approach to research on detransition, Rowan Hildebrand-Chupp (2020) discusses how gender critical feminists weaponize stories of detransition (where someone who is trans reverts to identifying as the gender they were pre-transition) in order to further their cause of delegitimizing trans people in a “gotcha! trans isn’t real” type of scenario. Hildebrand-Chupp analyzes detransition literature and research to shed light on these ‘canaries in the gender coal mine’ to discuss what we can learn from their experiences and how to best support them going forward. In Whose feminism is it anyway? The unspoken racism of the trans inclusion debate, Emi Koyama does an excellent job of arguing that the “no-penis” (biologically based) policies employed in trans exclusive spaces are inherently racist and classist, and how these spaces pit white middle-class women’s oppression against women of color and trans women.

At the present time, the accepted feminist discourse around sex and gender and trans inclusive politics is inadequate to overcome the divide. There is currently an abundance of literature being produced by academics about anti-trans feminisms, but they have yet to be systematically analyzed as a whole corpus and brought into conversation with one another. Further, no one has questioned whether the debate can be ended and analyzed how feminism can evolve by adopting a different perspective on the sex/gender divide. It is from this starting point that my dissertation takes off, as it hopes to bring new contributions to the academic fields of Sociology, discourse studies, and feminist theory by using a methodology that no one has used to study these discourses before (SKAD) and applying a theoretical approach (the politics of belonging) to analyzing the politics of sex and gender knowledge. The deconstruction of anti-trans feminist literature utilizing decolonial approaches to knowledge production can produce new analytical/theoretical frameworks for understanding anti-trans discourses and interrogate how belonging to specific social positionings of gender evolves within the protective confines of a specific life-world and how it is restricted within asymmetric power relations between those included and those remaining outside.

Aims and Objectives

There are a few objectives I would like to achieve with this dissertation. First, in my literature review, I would like to systematically review the scientific literature discussing Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminism in order to set out the political, social, and epistemic context in which this dissertation is being done. From there, I will draw attention to gaps in the literature (such as methodological shortcomings and unexplored theoretical territories) so as to make the case for the relevance of my unique, new contribution to the field. My approach will be the first to deconstruct anti-trans feminist discourses using the Sociology of Knowledge Approach to Discourse Analysis, drawing from a data set that focuses on anti- trans feminist published books and scientific literature (in contrast to other studies on TERF discourse which have only focused on social media, events, and journalism). It is at this critical point that this dissertation project seeks to overcome the divide between feminist by turning towards employing a new way of thinking about gender, sex, and transgender identity and their relationship to feminism and feminist theory; one that is committed to difference and embracing alterity through a decolonial praxis. In other words, my final objective would be to conceptualize an “anti-TERF” framework for understanding sex, gender, and transgender identity as they are ongoing negotiations of belonging.

Instead of viewing the discourse from the lens of identity politics, which all prior scholarly work has done, I will employ what Yuval-Davis calls the politics of belonging, which “relates to national belonging and the participatory politics of citizenship, entitlement, and status” (Lähdesmäki et al., 2016 p.239) and prompted by “migration, mobility, and displacement of people and trans-local and national boundary-crossing processes” (ibid.). The concept of belonging has been used to explore and make sense of a vast range of phenomena that scholars have found difficult to address using the concept of identity, which is exactly where debates about who can and can’t be a man or a woman get caught up in. Whereas ‘identity’ stresses the homogeneity of any given collective group (for example, women all being born with a certain set of biological markers), belonging stresses commonness, but not necessarily sameness (such that biology isn’t the only way one can ‘belong’ to the category of woman) (Pfaff-Czarnecka, 2011). To strengthen this line of thinking, I would also like to draw from Anzaldúa’s “Borderlands/La Frontera” (2007) in which she describes a borderland as “a vague and undetermined place created by the emotional residue of an unnatural boundary … it is in a constant state of transition … the prohibited and forbidden are its inhabitants” (p.17), as we can view transgender people as occupying a ‘borderland’ where notions of masculinity and femininity, maleness and femaleness, collide – drawing attention to the unnaturalness of a boundary (sex and gender politics) that is meant to keep them out. Looking at sex and gender discourse from a position that recognizes the entanglement of multiple and intersecting, affective and material, spatially experienced and socio-politically conditioned relations that are context-specific, I believe is a productive and fruitful way to reconstruct our understandings of the boundaries and borders of sex and gender and affect positive social change.

Through employing the Sociology of Knowledge Approach to Discourse as my operational methodology, I aim to develop a dissertation project that draws from and reworks the decolonial theories of difference and belonging, in order to address the following research questions:

- What is the historical trajectory (emergence, presence, and disappearance) of anti- trans feminist discourses and the way they change through time and space?

- What are the social actors, practices, means, and resources involved in the discursive conflict between feminists over transgender inclusion?

- What is their unfolding structuration of meaning, their impact, and the knowledge work they do in given social contexts?

- How are belonging and identity negotiated in anti-trans feminist discourses?

- What would an anti-TERF method for feminism and gender/lesbian/trans studies look like?

Methodology and Data

The methodological framework, or research program, I would like to use is that of the Sociology of Knowledge Approach to Discourse Analysis (SKAD), as I would like to further examine the systems of knowledge that produce anti-trans discourses. This is not a method that has not been used to study TERF discourses, and as a relatively new endeavor in the field of qualitative social research, it provides me with an opportunity to experiment with the ways in which it can be used to examine the discursive construction of symbolic orders which occur in the form of conflicting social knowledge relationships and competing politics of knowledge, such as those between anti-trans and pro-trans feminists. I would like to begin my dissertation with a broad discussion of anti-trans discourse in the Western world to set the stage to focus specifically on anti-trans feminist theories and perspectives. In order to understand what transphobia in feminism is I will analyze the ongoing and heterogeneous process of the production, circulation, and transformation of transphobia in feminist knowledge production. In order to deconstruct their discourses to find their model/pattern of argumentation which reproduces transphobia and identify mechanisms, instruments, and dispositifs of their discourse, I would like to use as my data the works of anti-trans feminists such as Janice Raymond (The Transsexual Empire, 1979), Germaine Greer (The Female Eunich, 1970 and The Whole Woman, 1999), Sheila Jeffreys (Gender Hurts, 2014), Kathleen Stock (Material Girls, 2021), Abigail Shrier (Irreversible Damage, 2021) and Holly Lawford- Smith (Gender Critical Feminism, 2022), as well as 5-10 publications from the Gender Critical Research Network, which is based at the British public university, The Open University.

I am choosing to use SKAD because it offers a conceptual and methodological framework for undertaking a variety of research questions that are interested in analyzing how discourse – the fluid network of language, power, and knowledge – construct our social realities, our understanding of who we (and others) are. SKAD provokes thinking about the roles that knowledge, knowledge production, knowledge hierarchies, and knowledge institutions play in social transformation (Keller, 2018). This knowledge is not only socially recognized and confirmed positive knowledge, but rather the totality of all social systems and signs which mediate between human beings and the world they experience through the functioning of systems and signs (Keller, 2018). It does not implement methods in a definitive or static way, instead emphasizing context-specific conceptualizations of discourse, which themselves are historically situated normative devices that are case- specific (Keller et. al, 2018). Discourses shape our every day life, guide us in our decision making, and construct public opinion, and SKAD requires us to reflect on the positionality of the researcher in relation to the discourse itself (Keller et al, 2018). In arguing for an inquiry into the production, circulation, and performance of processes of meaning making across societies, SKAD provides researchers with a space for research into questions of the social making of realities.

SKAD has promoted itself on being able to invite users to be creative while they use it, offering no pre-defined or static set of methods to be implemented (Keller et al, 2018). It offers a conceptual frame for studying the everyday processes of discourse in a vast array of academic disciplines and in many different cultural and socio-political contexts. This is why I believe it would be the appropriate choice for me to use in my dissertation. It would allow me to analyze the knowledge configurations that allowed two feminist camps to view gender and sex in such contrasting ways and the power-effects which emanate from them without tying me down to any particular theoretical standpoint; allowing for the interpretation of data to open the door to any and all possibilities of reconstructing feminist theory to be more inclusive.

Conclusion

Anti-transgender discourses are causing a major rift in the global feminist project for gender equality, as the debates about what social categories like “sex” and “gender” mean have deep historical roots that must be interrogated to understand how society responds to, and how these discourses impact and marginalize, transgender identities. Feminist theory provided transgender people with a way of understanding their gender identities and offered resistive political actions against a world that pathologized their difference; it is now being used against them to deny their ability to lead dignified lives as the borders of their bodies are being put up for debate and they are being ridiculed by people who would also benefit from the loosening grip of patriarchy. The crucial juncture of these debates within feminism is at the point of whether there is a universal, gendered subject by which social and political rights can be afforded to and if this is to be determined on the basis of how one identifies. New and reflexive ways of thinking are required to understand what it means to co-habit and get along with others who are different, and questions thus emerge about human identity and how it is constructed. As Offord argues, there is a connection between cosmopolitanism and questions of justice and equality in relation to gender (as a key organizing principle in society), as it is a space for “critique, creativity, border and boundary crossings, involving the possibilities of transformation through exchange and encounters with otherness” (2013, p.8). In an effort to better understand gender and sex difference, and build cooperation across such differences, a deconstruction of discourses which reproduce inequality combined with a fundamental re- thinking of transgender embodiment against feminist backlash is what I hope to encapsulate with my proposed work on this dissertation.

As a feminist and transgender scholar this topic has captured my personal and intellectual interest and it is one that I hope to contribute productive research and a fresh perspective to that I have yet to see approached by any other scholars working in the field of transgender studies in Sociology (and beyond). The divides between who is and isn’t an authentic woman have had disastrous consequences for people all over the world as the colonization of gender continues to leave its ugly mark upon different, non-normative bodies. The ongoing disenfranchisement and dehumanization of ‘Other’ bodies and ways of being means the work of academics is not done, especially because academia often fails to see the value in adopting decolonial perspectives in research projects. Working against the dominant world- making order of essentializing sex and gender and developing decolonial and subaltern ways of disentangling these systems of oppression can only lead to a more hospitable and equitable world for everyone.

References

Anzaldúa, G. (1987). Borderlands/La frontera: The New Mestiza. Aunt Lute Books.

Armitage, L. (2020). Explaining backlash to trans and non-binary genders in the context of UK Gender Recognition Act reform. Positive Non-Binary And / Or Genderqueer Sexual Ethics And Politics, (Special Issue 2020), 11-35. https://doi.org/10.3224/insep.si2020.02

Freeman, H. (2022). Why I stopped being a good girl. UnHerd. Retrieved 23 February 2022, from https://unherd.com/2022/02/why-i-stopped-being-a-good-girl/.

Hildebrand-Chupp, R. (2020). More than ‘canaries in the gender coal mine’: A transfeminist approach to research on detransition. The Sociological Review, 68(4), 800-816. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026120934694

Hines, S. (2020). Sex wars and (trans) gender panics: Identity and body politics in contemporary UK feminism. The Sociological Review, 68(4), 699-717. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026120934684

Jones, C., & Slater, J. (2020). The toilet debate: Stalling trans possibilities and defending ‘women’s protected spaces’. The Sociological Review, 68(4), 834-851. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026120934697

Keller, R. (2018). The sociology of knowledge approach to discourse: an introduction. In R. Keller, A. Hornidge & W. Schünemann, The Sociology of Knowledge Approach to Discourse: Investigating the Politics of Knowledge and Meaning-making (1st ed.). Routledge.

Keller, R., Hornidge, A., & Schünemann, W. (2018). Introduction: The sociology of knowledge approach to discourse in an interdependent world. In R. Keller, A. Hornidge & W. Schünemann, The Sociology of Knowledge Approach to Discourse: Investigating the Politics of Knowledge and Meaning-making (1st ed.). Routledge.

Lähdesmäki, T., Saresma, T., Hiltunen, K., Jäntti, S., Sääskilahti, N., Vallius, A., & Ahvenjärvi, K. (2016). Fluidity and flexibility of “belonging.” Acta Sociologica, 59(3), 233 247. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699316633099

LGB Alliance. (n.d.). Statement on reports that the UK Government plans to drop its previous proposals to reform the GRA. Retrieved February 15, 2022, from https://lgballiance.org.uk/gra/

Offord, B. (2013). Gender, sexuality and cosmopolitanism in multicultural Australia: a case study. GEMC Journal, 8, 6-21.

Pfaff-Czarnecka, J. (2020). From ‘identity’ to ‘belonging’ in social research: Plurality, social boundaries, and the politics of the self. European Scientific Journal ESJ, 16(39). https://doi.org/10.19044/esj.2020.v16n39p113

Tudor, A. (2020). Decolonizing Trans/Gender Studies? Teaching Gender, Race, and Sexuality in Times of the Rise of the Global Right. TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, 8(2), 238–253. Retrieved 24 February 2022, from.

Vincent, B., Erikainen, S., & Pearce, R. (2020). TERF wars. The Sociological Review.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Sociology and Transgender Studies: A Destabilizing Enterprise

a. From Object to Subject: Medical Pathologization and the Social Construction of Transgender

b. Challenging Gender Norms and the Binaries of the Social and Biological

c. Adopting Intersectional Approaches to the Diversity of Transgender Identity

d. Engaging with Transgender Politics and Activism

e. Pedagogical Strategies for Teaching Trans

f. Queering and Transing Methodologies in Sociological Research

g. Current Challenges and Future Steps for Sociological Theory and Research

3. Trans/Feminism: Mapping the Contours of a Contested Terrain

a. From Liberation to Exclusion: Feminist Histories and the Making of TERFism

i. Radical Foundations: Early Feminist Debates on Sex, Gender, and Trans (1960s – 1970s: Beauvoir, Raymond, Greer, Daly, Jeffreys)

ii. From Sisterhood to Separatism: The Rise of Cis-Women Only Spaces (West Coast Lesbian Conference and the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival (1980s – 1990s)

iii. The Queer Turn and Feminism’s Identity Crisis;

iv. The Great Rebrand: From TERF to Respectability Politics and the Rise of the ‘Gender Critical Feminist’ (2010’s – present)

b. Narratives of Fear: How Gender Critical Feminism Constructs and Institutionalizes Its Threats

i. The Stakes: Sex-Based Rights, Healthcare, & Gender Self-ID

ii. TERFism goes digital: How Online Spaces Became Radicalization Hubs (Mumsnet, Twitter, Substack)

iii. JK Rowling and the Pop-Cultural Normalization of TERFism

iv. From ‘Reasonable Concerns’ to Censorship Panic: The Academy and Free Speech as a Trojan Horse (Cancel Culture narrative, victimhood strategy, Kathleen Stock, EMMA Magazine/Alice Schwarzer)

v. Racialized and Classed Dimensions of the Debate

c. The Science Wars and Post-Truth Politics: Gatekeeping Medicine, Weaponising Detransition, Legitimizing ROGD, and Fairness in Sport

i. Medicine

ii. Sport

iii. ROGD

iv. Detransition

d. Dangerous Alliances: From Exclusion to Elimination

i. Anti-gender movements in Europe

ii. Partners in Prejudice: Gender Critical Feminism, the Far-Right, and Christian Nationalism

e. Trans Feminist Resistance: A Vision for the Future

i. Philosophical, Ontological, Epistemological Problems with TERF discourse

ii. Epistemic injustice

iii. The problem with identity politics: Status-Based Recognition

4. Theoretical Framework – Situated Disobedience: Power, Discourse, and the Borders of Belonging

a. Feminism on Fire: Situated Struggles and the Refusal of Innocence

i. From liberal inclusion to collective liberation

ii. Knowledge from the wound: Feminism as insurgent method

b. Discourse as Weapon: Power, Ideology, and the Battle over Meaning

i. The Force of Power: Discursive Struggles and Social Control

ii. The machinery of discourse: SKAD, dispositifs, and symbolic violence

iii. Naming, framing, and claiming: Ideology and the construction of the real

c. Coloniality Reloaded: Gender as a Tool of Empire

i. Inventing “woman”: Race, sex, and the making of modern subjects

ii. The violence of the norm: Racial capitalism, biopolitics, and the gender binary

iii. Unlearning the master’s tools: Decolonial feminist insurgencies

d. At the Edge of Belonging: Border Epistemologies and Excluded Lives

i. The border as wound and method: Mestiza, nepantlera, trans

ii. Belonging as exclusion: Regimes of recognition and the politics of purity

iii. Ungendered, unruly, uncontained: Living at the limits of the intelligible

e. Toward a Feminism That Destroys Prisons: Coalitions, Disidentifications, and Radical Care

i. Against the carceral impulse: Abolitionist and trans*feminist futures

ii. Building messy solidarities: Transversal politics and coalitional friction

iii. From critique to creation: Feminism as world-making praxis

f. Theory as Weapon: Assembling a Toolkit for Discourse Struggle

i. Fusing SKAD with decolonial and feminist disobedience

ii. Positioning, power, and epistemic resistance in anti-trans discourse

iii. Bordering, Belonging, and the limits of the Intelligible

5. Methodology – Lines of Struggle, Practices of Refusal: Inquiry as Situated Disobedience

a. Situated Knowledges, Embodied Standpoints

i. Feminist, Queer, and Decolonial Epistemologies

ii. Positionality, Accountability, and the Ethics of Situated Research

b. Disrupting Methodological Norms: Critical Approaches to Feminist Discourse

i. Beyond the Canon: Tracing the Field of Feminist and Trans Discourse Studies

ii. Methodological Ruptures, Omissions, and Possibilities

c. Conceptual Groundwork: Discourse, Ideology, Power, and Dispositifs

i. Discourse as Material and Symbolic Force

ii. Ideology and the Naturalization of Social Order

iii. Power/Knowledge and the Construction of the Real

iii. Dispositifs and the Institutionalization of Meaning

d. Mapping Meaning, Tracing Power: Operationalizing SKAD

i. Choosing the Field: Texts, Terrains, and Temporalities

ii. Feminist Media and TERF Worlds: A Multinational View

iii. Constructing the Controversy: Defining the Discursive Field

e. Critical Methodological Disobedience: Feminist, Queer, and Decolonial Interventions

i. Feminist CDA and Symbolic Violence

ii. Queer Analytics, Affective Power, and Epistemic Drift

iii. Border Epistemologies and Decolonial Rupture

f. Constructing the Archive: Data, Corpus, and Analytical Practices

i. Data Sources and Politics of Selection

a. Germany: Alice Schwarzer Editorial from 1984 and EMMA Magazine September/October 2023, Nr. 5 (370)

b. The USA: TransSisters: The Journal of Transsexual Feminism, Issue #7, Winter 1995 and blog post from dirtywhiteboi67 dated 9 March 2013

c. The UK: Kathleen Stock’s 2022 UnHerd Essay and J.K. Rowling Tweets from August 2024

ii. Sampling as a Situated Strategy

iii. Method Assemblage: Thematic Coding, dipostif analysis, positional mapping

g. Ethics in Conflict: Working Within and Against Structures

i. Researching Contested feminisms

ii. Ethics of Representation, Power, and Relational Accountability

iii. What Remains Unsaid: Limits, Silences, and the Politics of the Unknowable

h. Notes on Automation and Accountability: AI Use in Research Practice

i. Conclusion: Toward a Situated, Insurgent Inquiry

6. Data Analysis and Results

7. Conclusion